Implications for Finance, for Safety and for Life

FOCUS ON RISK

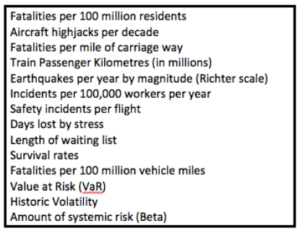

Financial professionals know a great deal about risk. The risk they know about is numerical, statistical, probabilistic, based on precedent and economic history. This is the world of economists, actuaries, underwriters and financial intermediaries. This analytic view of risk is designed to improve financial decision making. It might be referred to as Objective Risk; although, at every point, professional judgement is an important component.

FOCUS ON THE INDIVIDUAL

Subjective Risk, on the other hand, is something that financial professionals do not specialise in and know very little about. Rather than focusing on the risks ‘out there’, the dangers and uncertainties that may upset our plans, the focus of subjective risk is on the individual and how they are ‘wired’. It is about our risk dispositions: the personal and intimate experience of risk; the way that an individual reacts to it; their feelings and emotions; their resilience, expectations and the way our personal perceptions of risk are calibrated. How do these dispositions influence interpretations of events? How do they impact on the thousands of decisions a person makes every day at different levels of consciousness?

From a financial professional’s viewpoint, Subjective Risk is a source of error, irrationality, misunderstanding or bias. This subjective versus objective distinction is illustrated by a debilitating fear of flying (Subjective Risk); discounted because the chanced of death are a mere 10,000,000:1 (Objective Risk). However, Subjective Risk is of material importance – it drives all the decisions, choices and behaviours that create the statistics from which Objective Risk is calculated.

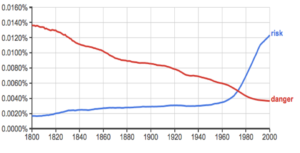

‘A Short History of Financial Euphoria’ is a classic text by the late Ken Galbraith, the renowned economist. He argued that ‘mass insanity’ has repeatedly gripped the financial world over the centuries. As waves of euphoria surge through the sector, sober judgement and restraint are swept away, all contrarian views are derided, and group-think rules.

This article argues that there are lessons to be learned by recognising the importance of Subjective Risk; turning the spot light from the risk ‘out there’ to focus on the people involved.

There are two options on the table as responses to the failure of financial institutions; Regulation and Organisational Development.

REGULATION

Much like Galbraith’s view of the cyclical pattern of failure in the world of finance, demands for ‘heavy touch’ regulation (to get things back on the rails) and ‘light touch’ regulation (to free up entrepreneurial spirit) alternate.

Whether financial regulation has been a success or not in the past is still argued by economists of different persuasions. The framework for regulation and constraint may have provided a basis for periods of relative calm but the financial world is in continuous flux and regulation seem never to have provided sufficient defences to stave off the next crisis.

Bear in mind, firstly, that Australia’s financial sector makes a $140 billion contribution to the economy and it employs around 50,000 people and, secondly, that wealth creation is not exactly a walk in the park. In turbulent, ever changing global markets, you can’t just choregraph success. Even Warren Buffet loses money ($4.3 Billion in one day when Kraft Heinz plunged more than 25%). Strait-jacketing the profession with punitive levels of regulation may not be the route to success for a sector that needs to maintain a delicate balance between creativity and social responsibility. Exactly how to regulate without damaging the industry is anything but straight forward.

“…we must not over-regulate such organisations and so impede their growth and innovation which are in turn so important for employment and the wider economy. It is extraordinarily difficult to get this balance right”

Martin Stanley, UK Civil Service

ORGANISATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

The alternative to externally imposed constraint is some form of internal development designed to improve the performance of the industry’s professionals. The array of corrective offerings made available by major consultancies have not escaped criticism. “It is clear that banks are wasting their money on “solutioneering” or expensive unproven programmes peddled by consultants to address risk culture” says Associate Professor Alessandra Capezio of the Australian National University in an article titled ‘No science’ behind bank risk strategies (Companies & Markets, 8 May 2019).

Culture has been reified as the essential focus for change. But culture is an elusive and intangible concept. It is a consequence of the traditions, processes and behaviours of those employed and, as an end product of a process, it cannot tangibly be altered except through the people of which it is composed. Organisational customs and practices are shaped by the attraction and selection of the people it requires ‘to do the job’. Successive waves of people passing through leave their mark in terms of their dispositions, habits and mores. In one influential and pragmatic view on organisational culture, it is ‘the people’ that ‘make the place’ (Benjamin Schneider, 1987, 2014). On this basis, if you want to influence organisational culture, then the current employees are the obvious levers of change.

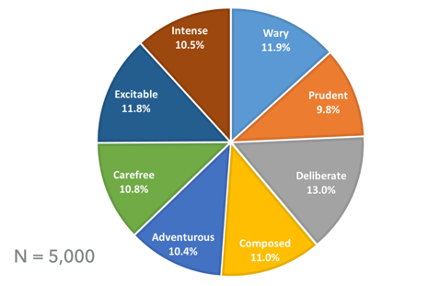

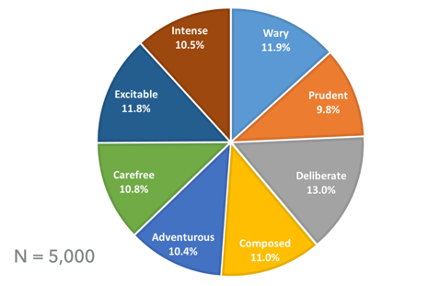

The mix of personalities in different industries certainly have a tangible impact on organisational ethos. Differences between, for example, a tax office, a public relations firm, a civil engineering practice or design agency are palpable. Different organisations and professions attract and recruit, in different proportions, people with various decision-making styles – their Risk Type. The traditional professions employ more Intense, Wary and Prudent Risk Types. The Deliberate Risk Type is attracted to jobs requiring precision, clear frameworks and narrow tolerances. While recruitment firms attract a predominance of Carefree Risk Types, they are very thin on the ground amongst Auditors, Air Traffic Controllers and Engineers.

To this extent, people do ‘make the place’ but organisations are hierarchical and individuals are not all equal in their influence or their responsibilities. Influence can be amplified by status, rank, qualifications, experience and length of service. Leaders and top management have the greatest cultural influence. Followers, by definition, are prepared to restrain their impact to some extent.

“The Wolves of Wall Street” This academic paper published in 2016 describes a 20 year project about bank managers and business models. In this research, 1,578 bank managers are tracked as they move jobs between 165 different banks. The researchers demonstrated how, like bees pollinating the flowers, the bankers take their risk dispositions with them wherever they go, influencing the business models of each management team they join. Financial Times investment banking correspondent Laura Noonan reported that the authors “could explain more of the banks’ decisions by looking at the personalities and the X-factor of the individual bankers than by looking at bonuses, compensation structures and other observable things like education and background”.

Any organisational change initiative needs to involve and to have the support, active endorsement and direct involvement of those that are the most influential – those at the top of the organisation. This is the lesson from ‘The Wolves of Wall Street’ study. FT’s Laura Noonan concludes, “what actually affects the risk culture is the character of the bankers at the very, very top”.

PEOPLE DEVELOPMENT

“Nature, to be commanded, must be obeyed” Francis Bacon.

The practical reality is that the kinds of change envisaged as a response to financial sector problems needs to dig deep. This is not a matter of tinkering at the edges. Broad generalisations about culture have to be realised through changes at the granular level; the level of the individual. To achieve this, it is essential to appreciate the realities of human nature and deal with them. The concept of ‘depth of Intervention’ (Cummings & Worley, 2009), recognises that management of change requires consideration of the psychological makeup and personality of employees and the challenges that the proposed change would require. This is the territory of Subjective Risk, discussed in the opening paragraphs – the kind of risk less familiar to financial professionals.

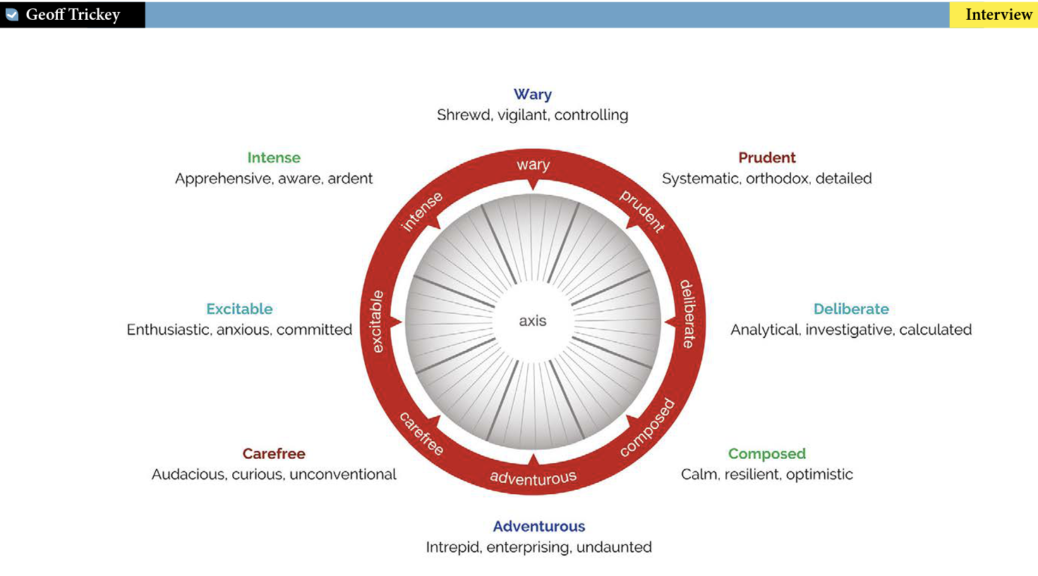

Risk dispositions are expressed in the ways that an individual makes decisions. The ‘tuning’ of their emotions combines with their cognitive style to create a very wide spectrum of risk taking and risk intolerance. The extremes appear quite unreconcilable; from low flying Mach 2 fighter pilots compared to those that are fearful of the mildest fairground rides; from those alarmed about any kind of insecurity to those who cash in their pensions to finance a sailing adventure.

“Decision-making draws on both the analytical and the emotional systems in the brain”.

Mark Walport (2014), Government Chief Scientific Adviser 2014.

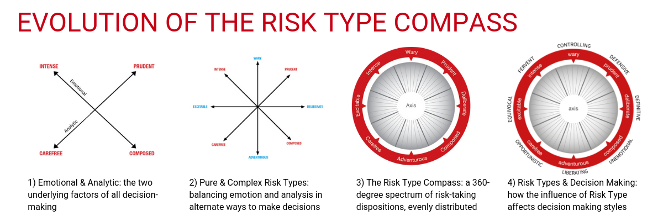

The consensus in current neuroscience challenges the dualism of Descartes (Antonio Damasio, 2006), recognising that two different neurological systems are always involved in the decision-making process – one is concerned with emotion and the other with cognition.

These two parameters provide the necessary framework for any measure designed to assess individual differences in risk taking behaviour. The aim is not to eliminate these differences. In fact, this diversity plays an important role in resisting group-think. The aim is to contribute to risk-aware decision making by raising awareness of the differences between the Risk Types and their respective advantages and disadvantages.

Cognition

This is all about our ‘need to know’; the need for coherence, to make sense of events and of life. Some (High Cognition) are troubled by ambiguity and uncertainty, welcome rules and structure or are prepared to follow procedures with painstaking detail. Others (Low Cognition) are questioning, challenging and excitement seeking. They embrace opportunities to try new ways of doing things. They prefer uncertainty to stability and are tormented by repetitive routine.

Emotion

Broadly, emotion is about visceral reactivity. Some individuals (High Emotion) are hyper reactive; easily aroused and easily bruised. Their passion and vigilance with regard to potential dangers or pit-falls make them the natural guardians of our species. Others (Low Emotion) seem almost imperturbable and take everything in their stride. They remain composed and unconcerned in situations that may terrify others.

Of course, the majority of people fall somewhere between these four extremes, but these provide the four ‘poles’ in a 360o spectrum of risk dispositions. There are infinite potential combinations of varying degrees of emotion and cognition and these are mapped throughout the radiating axes of the Risk Type Compass. For purposes of interpretation, the full spectrum is segmented into eight distinctive Risk Types.

In a recent Risk Management article, Michael Mazarr, senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation, also makes the point that “risk failures are mostly attributable to human factors”. Risk Types provide a systematic taxonomy supporting the quantification of human factor risk and differentiating individuals according to the ways they are disposed to make decisions.

The Risk Type Compass

The Challenge

Everyone working in the financial sector bring their risk dispositions, their Risk Type, into work with them every day. And they will vary considerably because, in the population as whole, the eight Risk Types are very evenly distributed. These core personality dispositions change very little over a working life time and they have a persistent influence on decision making. This is a fact that can readily be demonstrated. There are no right or wrong Risk Types (in fact their complementary nature is a significant survival asset for Homo Sapiens), but they have to be recognised and addressed. The known challenges to stability and clear thinking are ‘herd behaviour’, group think, risk-polarisation and cognitive dissonance. The required changes in Banking and Finance are not going to be achieved through exhortations ‘to do better’, by herding everyone through a course on integrity, running ‘values’ campaigns, posting slogans to keep staff ‘on message’ or optimistic annual report statements.

Prevalence of the eight Risk Types

The Approach

The antidote to group-think is to ensure that there is diversity in risk dispositions around the table, so that issues are considered from several perspectives and that each person has the opportunity to state their point of view – that there is always a ‘devil’s advocate’ presenting a contrarian view. This may sound adversarial, but in team sports there are defenders and attackers on the same team chasing the same goals. The defenders are alert to danger, the strikers alert to opportunity – so long as the aims and allegiances are aligned, diversity of risk dispositions makes the team stronger and more effective. On the other hand, the loss of an all too comfortable guaranteed consensus of like-minded colleagues may take some getting used to, but that too is do-able.

What the Risk Type Compass brings to the table is the ability to get a ‘fix’ on the risk dispositions that make some people risk averse and others carefree or adventurous and everything else in between. Every Risk Type has its contribution to make. The ability to utilise these insights and to bring them to fruition benefits everybody. Individuals then have a well-defined foundation on which to develop risk-awareness and personal development. Risk Type strengths and challenges write a personal agenda for risk-aware decision making. At the group level, appreciation of the balance or distinctiveness of the group dynamics, highlights potential blind-spots and biases and increase team effectiveness. At an organisational level, the Risk Landscape highlights the relative risk dispositions of teams/ divisions/ departments and allows cross-department comparisons, strategic planning, decisions based on team audits, staff redeployment and rebalancing.

Peter Drucker is attributed with the most frequently cited aphorism of business wisdom:

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it”

The aim of organisational change cannot be to alter people’s nature. A better and more realisable objective is to recognise this reality, to address it, and to turn it to advantage. There are no right or wrong Risk Types. Each makes its own distinctive contribution to survival. The aim now is no different than it has always been – to maintain that crucial balance between the risks and the opportunities.

CONCLUSIONS

Within the totality of risk there is a crucial distinction between ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ risk. The Finance world is well versed in the former, but not in the latter. Banking crises arise, a) because financial markets are inherently volatile (objective risk), and b) because the industry decision making is vulnerable and susceptible to herd behaviour (subjective risk). The capability to identify and reliably measure the risk dispositions of individuals across the organisation creates, for the first time, a potent framework for organisational and personal development.

Diversity of risk dispositions in teams, groups and decision-making bodies – whether in the board rooms, amongst the execs, traders or interns – is a common sense antidote to group think.

Geoff Trickey, June 2019

REFERENCES

Domasio, R., (2006). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain. Random House.

Bernard Burnes (2014): Understanding Resistance to Change – Building on Coch and French. Journal of Change Management, DOI: 10.1080/14697017.2014.969755

Hagendorff, J., Saunders, A., Steffen, S., & Vallascas, F. (2015). The Wolves of Wall Street? How bank executives affect bank risk taking, SSRN eLibrary (USA).

Michael j. Mazarr (2016) “The True Character of Risk”, Risk Management Magazine

Schneider, B., 2014 (Editor) The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Climate and Culture (Oxford Library of Psychology), Oxford University Press, 2014

Shneider, B., (1987) “The People Make the Place”, Personnel Psychology, 40 (3), 437-453

Tett, G (2009) “Fool’s Gold: How Unrestrained greed corrupted global markets and unleashed a catastrophe”, Hachette

Walport, Mark (2014) “INNOVATION Managing risk, not avoiding it” Annual Report of the Government Chief Scientific Adviser.