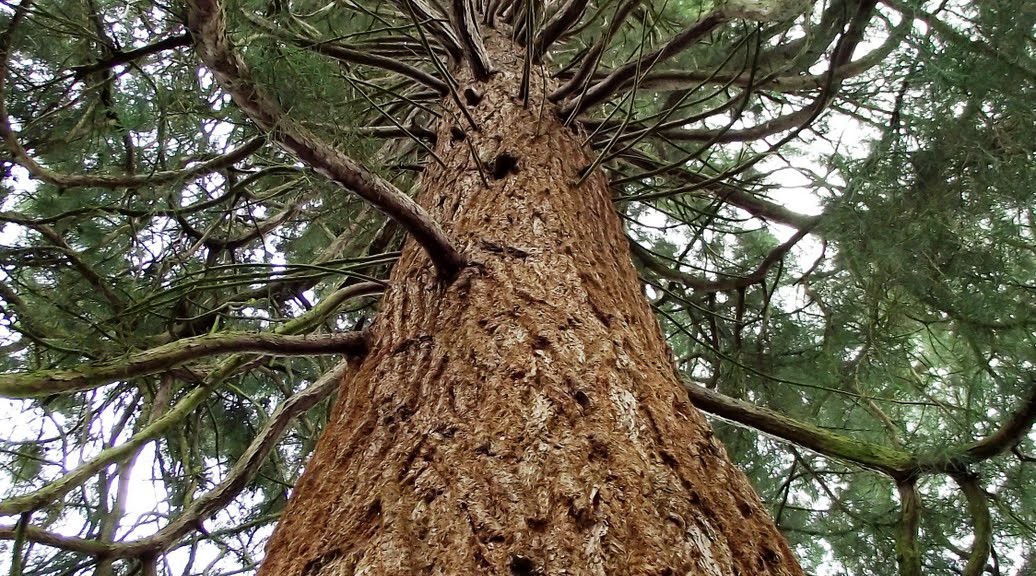

For the past three years I have been trying to grow a lawn under a massive, 80-foot-high Wellingtonia Pine, which completely dominates my garden. With three young children, we need something more useable than the existing area of dirt and tree debris. I have tried everything and put in endless hours of tender loving care, but I still face a barren expanse of brown mud each spring.

The tree surgeon that called about my problem tree advised that, without a major genetic engineering breakthrough, I was flogging a dead horse. Apparently, however much I fertilise, dress, weed or aerate the soil, all my efforts to make the grass grow will be to no avail. It seems that Astro Turf may be the only answer!

I tell this story, firstly, because my failure was certainly not due to any lack of motivation or effort; I was determined to succeed, but my goals and my strategy were seriously flawed. Secondly, my garden saga draws parallels with the development of people in the workplace and the situation faced at all levels by employers, trainers and potential trainees.

The question is: to what extent is one fighting with nature in trying to shape and mould people to fit the demands of a particular role? Is training able to improve the performance of an employee and, alternatively, to what extent can the limited skills of a given individual be compensated for by using alternative strategies? Within the wider context of personal career development, when should the agenda change from helping the individual shape up in his existing role, to looking for an alternative role in which that individual will flourish, become effective and feel fulfilled?

These questions are central to any talent-management programme (for the organisation), and to any personal development programme (for the individual).

Every job makes its own demands and a good ‘fit’ between the job and the temperament of the individual is highly desirable. You can blow the entire training budget on making Sarah a good sales person and never succeed, because she is quiet, likes to keep to herself and finds all but the most familiar social situations difficult. Similarly, John is highly imaginative and gregarious and no amount of training will shoehorn him into a repetitive job in which there are no opportunities for social engagement. Henry is irritable, sensitive to criticism, moody and outspoken.

Because these characteristics are deep rooted, for those born apprehensive, anxious or fearful, any effort to equip them for a successful career in a customer service role will be doomed to the same lack of success as I face in the struggle to nurture a lawn.

It’s not quite as simple as that, of course. There is an important distinction to be made between the development of discreet and specific knowledge or skills, and the development of more basic aspects of a person’s temperament or personality.

For example, you can teach most people keyboard skills but it’s much more difficult to change their concentration span or their accuracy and attention to detail, because these are pretty much hardwired characteristics. Some people will hit their ceiling typing speed earlier than others, and even their appreciation of layout and presentation is influenced by innate aptitudes.

Self-knowledge

The essential elements for any personal development programme are goals – what you intend to improve – and strategies – how you are going to achieve them. The first stage in this planning process is for the individual to be aware of his assets and limitations in the first place.

The answer to the familiar question ‘how many psychiatrists does it take to change a lightbulb?’ is ‘one – but the lightbulb has got to want to change.’ Self-knowledge is the essential first step. A realistic, ‘face the facts’ appraisal of talents and limitations is the necessary starting point if a personal development strategy is to be effective.

The difficulty for those wishing to appraise others’ training needs is that we are actually very poor at summing one another up. The success rate of unstructured face-to-face interviews, for example, proves to be little better than chance when it comes to predicting job success. Open any tabloid newspaper any day of the week and you will find stories illustrating how misguided we can be about one another. A tendency to see others as more like us than they really are, and a tendency for others to ‘tune in’ to these expectations and try to match them, further obscures the picture.

Personality profiling and other formal assessment methods have a critical role to play here. We are all different in our temperament and aptitudes and there are some things that we will never do well, and some roles in which we will either fail or be miserable because of deeply rooted aspects of personality that cannot easily be changed.

Personality assessment can help us understand whether our temperament would be an asset in a role, and to what extent any incompatibility can be compensated for by training or by developing ‘workaround’ strategies.

In terms of my pine tree, is there an Astro Turf alternative? Once we have gained some insight into our assets and limitations, we can decide on some realisable goals. The next step then is to decide on the strategies by which they may be achieved.

Strategy one: exploiting strengths

The easiest way to improve performance is to focus on the further development of existing talents, rather than focusing on areas for which you have little ability and lots of frustration. By working to take high points to an even higher level, we are working ‘with the grain’, with natural dispositions and high potential.

Whatever the details of one’s personality profile, there will always be aspects that will con- tribute to success in one context or another. By identifying the elements in which we are strongest and making the most of these, we have our greatest opportunities for success.

The first point to ask yourself, therefore, is: “What assets do I have in relation to this job?” Although this might seem a very straightforward question, there is a rather surprising difficulty. People will often undervalue their talents and take them for granted. Because they are as familiar as the air they breathe, they may be oblivious to their worth and see nothing exceptional about them.

A talent could be almost any distinctive characteristic. Yes, it could be a great singing voice, artistic talent or spelling or numeracy, but the things we do well will not necessarily fall so neatly into an obvious ‘talent’ category.

For example, one may approach things in a distinctively rational and logical way; or have a fluency with ideas that others would envy; or a talent for engaging others, spotting discrepancies, lifting the mood in a group, or solving practical problems; the list is endless.

Recognising our assets will take us a critical step forward.

Before considering what you should do in areas in which you are relatively weak, take performance associated with your strengths to a new level first and the gaps that are still left to fill will become less significant.

Strategy two: pushing the boundaries

Whatever our ‘hardwired’ characteristics, we are all able to control or manage our behaviour to some extent. We do this when we vary our behaviour to suit the circumstances – being very controlled at a job interview, or being wild at a stag party or hen night. Depending on our motivation (our interest, determination or experience), we can perform above or below our natural or most typical level.

Strategy two is to raise our game, to use feedback or assessment results to build self-awareness and to focus on improved performance. Although you won’t change your basic nature, you may be able to improve within the specific conditions of your work.

Familiarity with the role, its specific focus, knowledge base and routines all help to create a ‘comfort zone’ within which you will look good!

Strategy two should always be an important consideration. Don’t be too ambitious. Try to find a supportive, less demanding situation in which you can begin to build the confidence that will eventually be required.

In your own case, strategy two may be designed to make you calmer and less impulsive, more independent, more tough-minded, more patient, or a change in any other aspect of your temperament. But there will usually be a limit to the extent that you can control or develop your temperament in this way. Beyond that limit, you will need to consider strategy three.

Strategy three: compensating and working around

Strategy three is concerned with developing ‘workarounds’: techniques or arrangements that compensate for the part of your make- up that is difficult or impossible to change significantly, or enough to make a sufficient performance difference.

Again, the first step is self- awareness. You cannot change unless you recognise the need to change, and a personality assessment will help you to appreciate where your talents lie and where your temperament will be at odds with the demands that you face. Strategies will usually involve approaching the job in a different way, or working with colleagues in a different way, or changing the balance within a role so that you are playing to your strengths.

You may do more of this, but less of that, and achieve your targets in that way. Or, you may exploit related aspects of a role to minimise dependency on the characteristics that you are having difficulty developing.

In practice, the three strategies will complement and reinforce each other; as you strive to achieve your goals, you will learn to adopt them to the best effect. You may also realise that sometimes you need to go back to the drawing board and review your goals.

The tree surgeon suggested we seek planning permission to lop the lower branches of our protected Wellingtonia Pine, letting the light and warmth of the sun into the garden. We tried, and we failed again. Transformation only came as we appreciated that we would never beat nature in that particular battle. Abandoning the lawn, we designed a beautiful tree house that would thrill any child, with prospects for sleepovers and adventure games.

The limitations imposed by the tree have been turned around. In the new scheme of things, the tree is no longer the problem – it is the star, centre stage, and the basis for transforming a child-unfriendly area into a wonderful play space. As ever, nature had the final say.