Subjective risk is often overlooked by risk managers as being too difficult to deal with. Yet having a diversity of risk dispositions on a team can be a great strength.

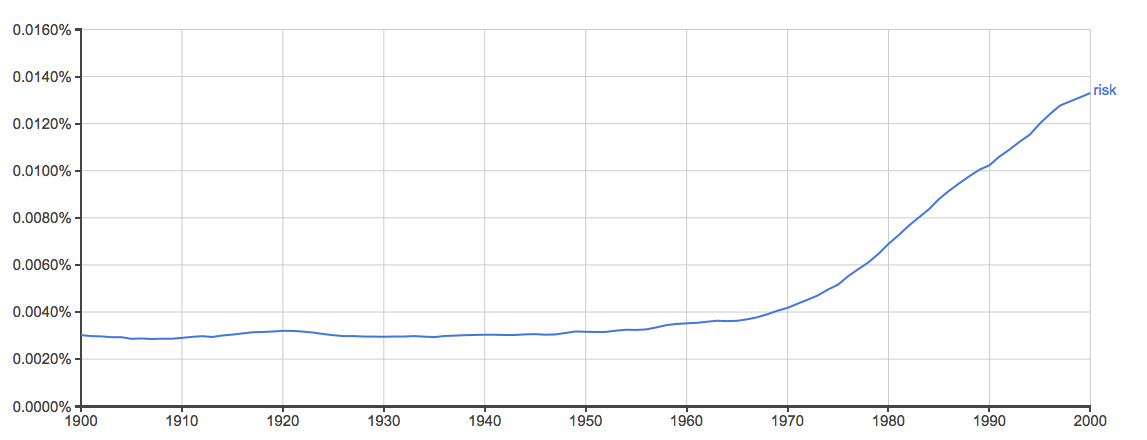

Financial professionals know a great deal about risk. The risk they know about is numerical, statistical, probabilistic and based on precedent and economic history. This is the world of economists, actuaries, underwriters, financial intermediaries and many risk managers. This analytic view of risk is designed to improve financial prediction and decision-making. It might be referred to as objective risk – although, at every point, professional judgment is a necessary component. Subjective risk, on the other hand, is something that financial professionals do not specialise in and often know very little about. Rather than focusing on the dangers and uncertainties that may upset our plans in the outside world, subjective risk focuses on individuals and how they are wired. It is about individual risk dispositions: the personal and intimate experience of risk; the way that an individual reacts; their feelings and emotions; and their resilience, expectations and the way personal perceptions of risk are calibrated. How do these dispositions influence interpretations of events? How do they impact on the thousands of decisions a person makes every day at different levels of consciousness? From a risk manager’s viewpoint, subjective risk is often discounted as a source of error, irrationality, misunderstanding or bias. The distinction between subjective and objective risk is illustrated when someone discounts a debilitating fear of flying (subjective risk) because the chances of being killed are a mere 10,000,000:1 (objective risk). But subjective risk is of considerable material importance. It is what drives all the decisions and often erratic behaviours that create the events and statistics from which objective risk is retrospectively calculated. Risk managers could learn important lessons by focusing on this often-neglected perspective.

Regulation vs organisational development

The two main options on the table to address the failure of financial institutions focus on regulation and organisational development. In a short history of financial euphoria, the late, renowned economist Ken Galbraith argued that “mass insanity” has repeatedly gripped the financial world over the centuries. As waves of euphoria surge through the sector, sober judgment and restraint are swept away, all contrarian views are derided and groupthink rules. Galbraith’s view of the cyclical pattern of failure in the world of finance is mirrored in alternating demands for heavy-touch regulation (to get things back on the rails) and light-touch regulation (to free up entrepreneurial spirit). Whether financial regulation has or has not ever been a success is still argued by economists of different persuasions. The framework for regulation and constraint may have provided a basis for periods of relative calm, but the financial world is in continuous flux, and the results seem never to have provided sufficient defences to stave off the next crisis. The alternative to externally imposed constraint is some form of internal development designed to improve the performance of the industry’s professionals. The array of such corrective offerings made available by major consultancies have not escaped criticism. “It is clear that banks are wasting their money on ‘solutioneering’ or expensive unproven programmes peddled by consultants to address risk culture,” Associate Professor Alessandra Capezio of the Australian National University has recently written. Culture change has been reified within the financial sector as the essential focus for change. But culture is an elusive and intangible concept. Unless it can be defined operationally, this is just kicking the issue into the long grass. Culture is a consequence of the traditions, processes and behaviours of those employed and, as an end product of a process, it cannot tangibly be altered except through the people of which it is composed. Organisational customs and practices are influenced by the attraction and selection of the people it requires to do the job. Successive waves of people passing through leave their mark in terms of their dispositions, habits and mores. In Benjamin Schneider’s influential and pragmatic view on organisational culture, it is the people that make the place. On this basis, if you want to influence organisational culture, then the current employees are the obvious levers of change. The practical reality is that the kinds of change envisaged as a response to financial sector problems need to dig deep. This is not a matter of tinkering at the edges. Broad generalisations about culture have to be realised through changes at the granular level – the level of the individual. To achieve this, it is essential to appreciate the realities of human nature and deal with them. The concept of “depth of intervention”, outlined by TG Cummings and CG Worley in 2009, recognises that management of change requires a consideration of the psychological makeup and personality of employees and the challenges that the proposed change would involve for them. This is the territory of subjective risk – the kind of risk less familiar to financial professionals.

Emotion and cognition

Trends in current neuroscience recognise that two separate neurological systems are involved in any decision-making process – one is concerned with emotion and the other with cognition. For example, the neuroscientist Antonio Damasio says that interactions between these systems create the structures for a wide spectrum of individual differences that are expressed in personality and in risk-related behaviour. Decision-making at a deep level is, therefore, tied to emotional, subjective influences. Cognition concerns our ‘need to know’, to make sense of events and of life. This is a rigid priority for some, but the loosest of frameworks for others. The former are troubled by uncertainty and welcome rules and structure. The latter are curious and embrace new opportunities and new ways of doing things. Emotion is about strength of feelings. Some are anxious and easily unnerved. Their hair-triggered vigilance makes them the natural alarm raisers of our species. Those at the other extreme remain calm and composed in situations that would terrify others; they are the last to run for cover. The majority of people fall somewhere between these four extremes, which also provide the basis for a compass-style model of risk dispositions. Interaction between emotion and cognition creates a rich variety of dispositions that are mapped throughout the 360º spectrum of a Risk Type Compass® – shown here, for example, on a spectrum segmented into eight distinctive Risk Types. Risk Types provide a systematic taxonomy supporting the quantification of human factor risk and differentiating individuals according to the ways that they deal with risk and are disposed to make decisions.

Challenges

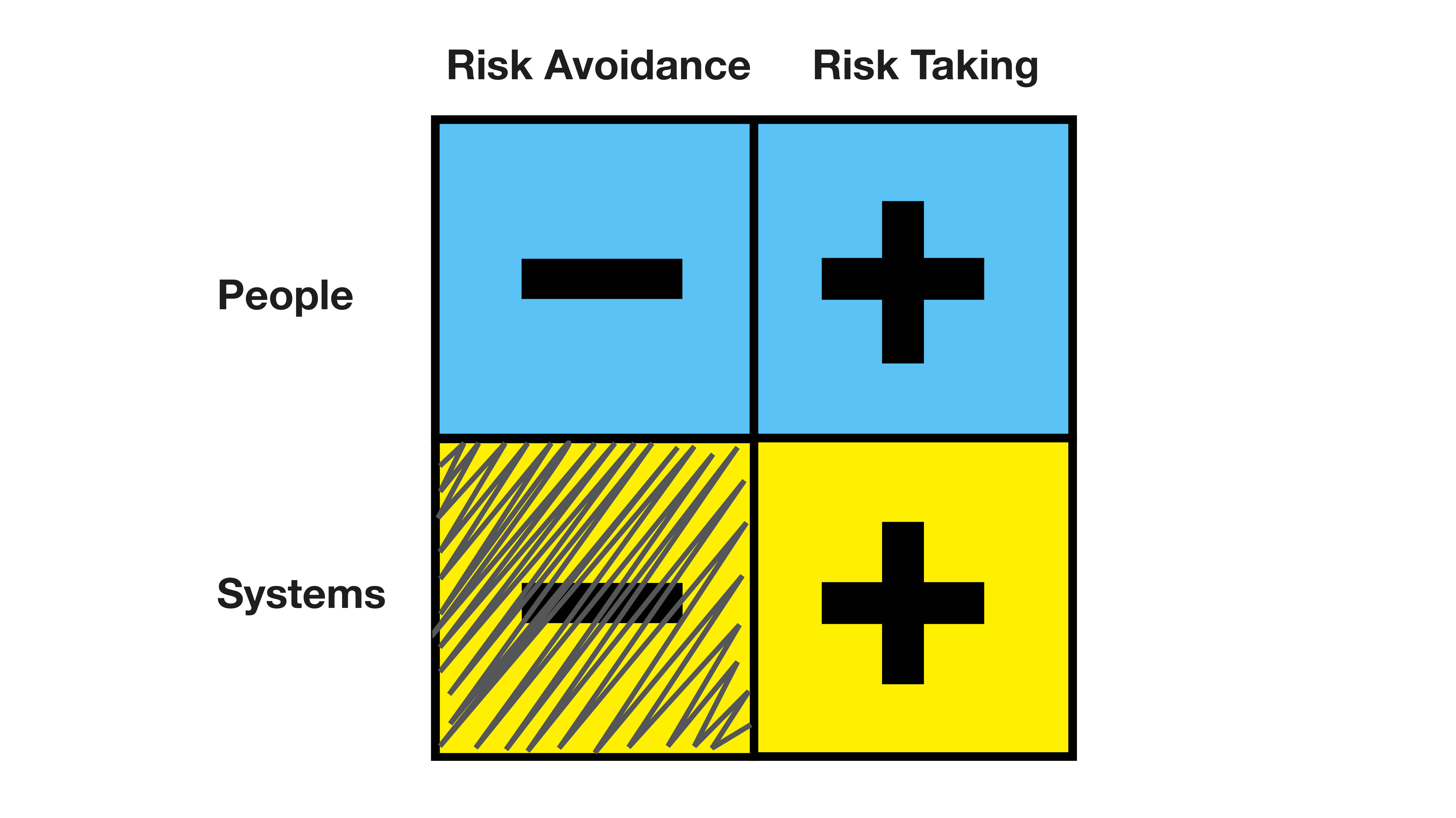

More than a million people are employed within the UK financial sector, and every one of them brings their risk dispositions into work with them every day. Teams and working groups will vary considerably because in the population as a whole the eight Risk Types are evenly distributed. These core personality dispositions change very little over a working lifetime, and they have a persistent influence on decision-making. There are no right or wrong Risk Types, but to harness these diverse talents, they need to be recognised and addressed. The changes required in the financial sector are not going to be dealt with by exhortation to do better, by running courses or by campaigns, slogans or optimistic annual report statements. The known challenges to stability and clear thinking are herd behaviour, groupthink, risk-polarisation and cognitive dissonance, factors on which Risk Type can wield significant influence.

The approach

Ensuring that there is diversity in risk dispositions around the table acts as an antidote to groupthink. It allows issues to be considered from several perspectives and encourages the expression of contrarian viewpoints. This may sound adversarial, but in team sports there are defenders and attackers on the same team chasing the same goals. The defenders are alert to danger, the strikers alert to opportunity – so as long as the aims and allegiances are aligned, diversity of risk dispositions makes the team stronger and more effective. This may be less comfortable than a cosy consensus among like-minded colleagues, but it is likely to be a safer bet. Every Risk Type has its contribution to make. The ability to utilise these insights and to bring them to fruition benefits everybody. Individuals then have a well-defined foundation on which to develop risk-awareness and personal responsibility. At the group level, appreciation of the balance or distinctiveness of the group and its dynamics highlight potential blind spots and biases and increases team effectiveness. At an organisational level, the risk landscape highlights the relative risk dispositions of teams, divisions and departments and allows cross-department comparisons, strategic planning, decisions based on team audits, staff redeployment and rebalancing. The aim of organisational change cannot be to alter people’s deeper nature. A better and more realisable objective is to recognise this reality, to address it and to turn it to advantage. Each Risk Type makes its own distinctive contribution to survival. The aim now is no different than it has always been – to maintain that crucial balance between risk and opportunity, to succeed and to survive. As this article has argued, within the totality of risk there is a crucial distinction to be made between objective and subjective risk. The financial world is well-versed in the former, but not in the latter. Banking crises arise, firstly, because financial markets are inherently volatile and unpredictable (matters of objective risk), and secondly because judgment and decision-making are susceptible to the risk dispositions of individuals throughout the organisation (matters of subjective risk). The possibility of identifying and reliably measuring the distinctive risk dispositions of any individual contributes to a potent conceptual framework within which to manage human factor risk. This is a vehicle of proven effectiveness in the development of individuals, the audit and development of teams and a reliable, pragmatic and objective basis for risk culture analysis. The Risk Type Compass® provides a taxonomy and a working vocabulary. Diversity of risk dispositions within any team or organisation is a potential problem if not recognised, and a potent survival factor when it is. Appreciation of the complementary nature of the different Risk Types and their even distribution are levelling factors that make the objective of mutual respect for different risk dispositions eminently realisable. The legacy of the financial crisis has been toxic in its focus on deficiencies, blame, uncertain boundaries of acceptability and preoccupation with integrity. Maybe what is needed is a fresh start and the openness, optimism and inclusiveness implied above. Combined with a purposeful culture of coaching and development, this might be a good place to begin.

First published in Enterprise Risk.