Confidence is a very reassuring characteristic. Whether seeking advice or looking for leadership, we appreciate a response that is unequivocal and decisive. At times of uncertainty and anxiety, we look for someone who, at least in appearance, has a confident and optimistic view about what we should do. When the plane is being buffeted by turbulence on your holiday flight, chances are that you will keep an eye on the cabin crew; are they remaining relaxed, smiling and optimistic? A confident demeanour is always reassuring.

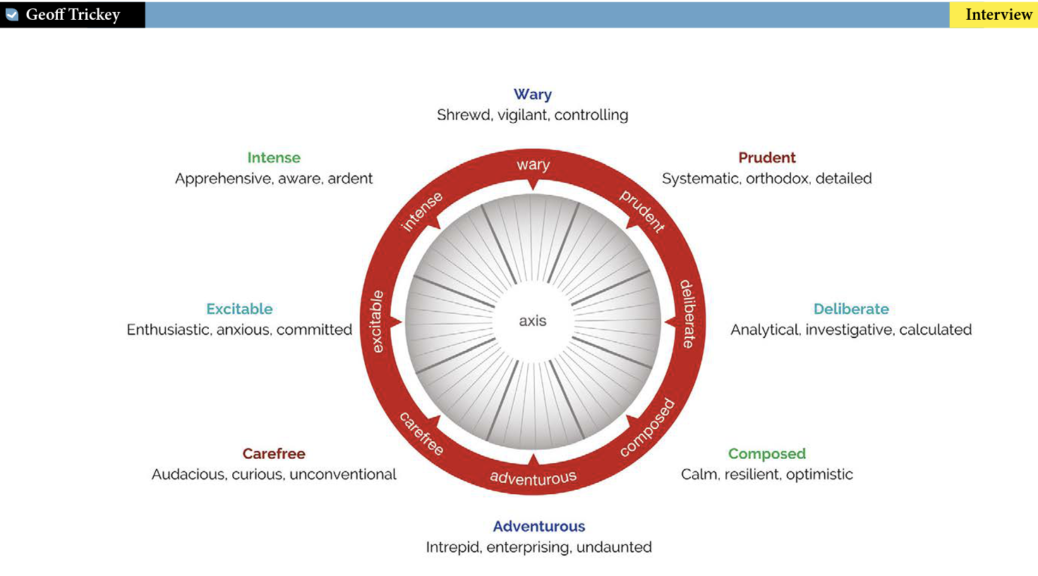

Psychological Consultancy Ltd (PCL) has been conducting research into personality for two decades. In its research publication, ‘Made to Measure’, PCL reflects the view that personality assessment is capable of very accurate descriptions of individuals and ‘confidence’ is a significant part of that picture. The appeal of confidence arises because, in personality terms, it is typically accompanied by optimism and calmness. Some people just seem to have it. For others it can seem a battle that is rarely won.

Self-confidence is one of those competencies often cited in job descriptions and elaborated as being socially self-assured, ready to express opinions and happy to take on responsibilities. However, our ‘Made to Measure’ research shows that self-confidence is one of the personality traits that can be hard to find. This is reflected by the choice of over 14,000 Amazon book titles on the subject – everything from self-help promises of improved self-esteem to success in public speaking, power and influence.

Confidence comes in different guises and its not all good news.

Some have the innate personality characteristics that support this behaviour. Calm babies, by and large, become calm and confident adults. At their best, these people are emotionally imperturbable and unreactive, so they weather any storm and keep their heads when others may be in a state of panic. On the down side they may seem insensitive to the needs of the more tortured soles that surround them – they never seem to quite understand what all the fuss is about. People like working with them because they are reliably consistent and predictable in their mood. Individuals know where they stand with them, and they seem even handed and fair because their demeanor is the same with everybody. Depending on other aspects of their personality, these characteristics are often viewed as fearlessness (unperturbed by risk) or insensitivity (showing little emotion).

A second group at this extreme end of the spectrum is also populated by those who’s confidence is fueled by a deeply rooted assertiveness and egotism. In a work situation they have a need to ‘trump’ others in any conversation in terms of their experiences and achievements and to assert their opinions and authority. This apparent abundance of confidence is likely to be rewarded by career progress. As managers they are likely to impress their superiors but their subordinates may regard them as arrogant, manipulative, blaming others and taking all the credit.

The third, broadest and largest category by far includes those who become confident through experience. People who are not naturally sure of themselves, even some who are low in self esteem, may become very confident because of their mastery in their own field. Such people often master the art of public speaking even though this is the top source of anxiety for most people. Becoming knowledgeable in a specialist area or skilled in some way contributes to self-esteem and success breads confidence (as any sports team knows). However, this kind of confidence is selective. Although there may be a general rise in self-esteem, the peak of confidence will remain in the domain where it was earned. The most confident and decisive may revert to being hesitant and unsure in less familiar territory outside their ‘comfort zone’.

These personality descriptions have implicit long-term predictive value. As we settle into our various roles, people are increasingly likely to display the dispositions captured by a personality assessment. By now, you will have some idea where you fall in this spectrum of confidence. So what, if anything, can you do if you want to change things? Whatever our personality characteristics, we are all able to control or manage our behaviour to some extent. We do this when we vary our behaviour to suit the circumstances – being very controlled at a job interview, or being wild at a stag party or hen night. Depending on our motivation (our interest, determination or experience), we can perform above or below our natural or most typical level.

Over many years of professional practice, the PCL team has identified four key strategies for personal development. These are not mutually exclusive and any development programme will embrace one or more of the following:

Strategy 1 – Build on your strengths

The easiest way to make a difference is to focus on the approaches and methods that you are already good at. These will, almost by definition, be strategies that you have a natural potential for. The question is, “do you know what your strengths are?” Surprisingly, people often don’t. When something comes very naturally to you and requires little effort, there is a tendency to under value it’ to assume that it is ‘normal’ for everyone and unexceptional. Some people have a ‘natural’ potential for spelling. You may have met people who seem able to spell everything, and with little effort (even exhilarate, acrylic and diarrhoea)! Others can sing, write well or are artistic, yet never exploit these talents.

Strategy 2 – Push the Boundaries

Strategy Two then, is to raise our game, to use feedback or assessment results to build self-awareness and to focus on improvement. Although you won’t change your basic nature, you may be able to improve within the specific conditions of your work. For example, a shy, quiet person cannot be turned into an extravert, but they can learn how to deal with the specific social requirements of their role very effectively – even exceptionally well. Familiarity with the role, its specific focus, knowledge base and routines all help to create a ‘comfort zone’.

Strategy 3 – Compensate and work around

Strategy Three is concerned with developing “work arounds”; techniques or arrangements that compensate for the part of your make-up that is difficult or impossible to change significantly, or enough to make a sufficient performance difference. Again, the first step is self-awareness. You cannot change unless you recognise the need to change and personality assessment will help you to appreciate where your talents lie and where your temperament will be at odds with the demands of your role. Strategies will usually involve approaching the job in a different way, or working with colleagues in a different way, or changing the balance within a role so that you are playing to your strengths. You may do more of this, but less of that, and achieve your targets in that way. Or, you may exploit related aspects of a role to minimise dependency on the characteristics that you are having difficulty in developing.

Strategy 4 – Reign in the excesses

Strategy Four is concerned with the tendency to ‘over play’ ones strengths; or ones perceived strengths; recycling the strategies that have worked for you in the past in the expectation that success will follow as it did before. Just as we may take the most effective aspects of our personality for granted, we also tend to be deaf to criticisms about our less effective characteristics. In fact, people are often quite indulgent of the features that are a turn-off to others. Some psychologists have suggested that parenting may have played a part in this, indulging, encouraging and rewarding behaviours that are ‘cute’ in children but monstrous in adults!

Of course, in practice, all of these strategies will complement and reinforce each other in promoting the desired goals. There is no quick fix for developing self-confidence; it requires commitment to self improvement and a sustained effort. The benefit of psychometric assessment is that we can identify for ourselves our key personality characteristics. Knowing who we are is the first step in understanding how to find a particular role or a career that draws on our strengths and supports and brings out what we are naturally good at. Equally, we can identify the challenges; addressing those elements of our personality that might be holding us back.

You are who you are in the sense that you have a unique combination of natural dispositions. On the other hand, you are also a free agent, a sentient being with free will. How you play the hand that you were dealt with is up to you – it will also write your autobiography.

Geoff Trickey, Managing Director, Psychological Consultancy Ltd (PCL)

Fist Publication: Fresh Business Thinking 2015