Have you been asked to complete a Happiness questionnaire yet? Happiness for everyone is apparently the new political currency – so, if you haven’t already you soon will. In 2010, the British Prime Minister announced that subjective wellbeing would be a major government goal; “We’ll start measuring our progress as a country, not just by how our economy is growing, but by how our lives are improving; not just by our standard of living, but by our quality of life,” (David Cameron). A UN resolution of the following year encourages member states to pay more attention to the pursuit of this goal. And launched its World Happiness Report in April 2012.

Of course, similar aims have been addressed in the US constitution since July 4th 1776 with its declaration of the right to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness”. In fact, the debate has to be at least 2000 years old. The pursuit of happiness was also high on the agenda for the philosophers of ancient Greece. Aristippus of Cyrene considered pleasure as the sole intrinsic good and introduced us to Hedonism. All the major religions, of course, also address the happiness issue with aspirations for ultimate bliss in the afterlife and through a joyful life of service and self-sacrifice.

The graphic charts the prevalence of the term ‘happiness’ in printed texts in America since 1800. Can this really mean that interest in happiness has actually been declining? The downward trend is so distinctive that it certainly demands some kind of explanation. Or, is this simply a function of some statistical anomaly? As with any debate about ‘happiness’, there are many reasons why it may be difficult to come to any clear or consensual conclusions.

Happiness Methodology

The methodology of the big players in happiness research, like the Wellbeing Programme at the LSE Centre for Economic Performance (CEP), involves the assessment of ‘subjective wellbeing’ by the use of surveys and questionnaires. CEP considers that happiness can be captured by four questions related to: 1. The individual’s overall satisfaction with life, 2. Whether they considered the things they were doing to be worthwhile, 3. Their recent experiences of happiness, and 4. Their experiences of anxiety.

Within HR and business psychology, the expression of this interest has focused particularly on job satisfaction and employee engagement. The principle methodology is the use of questionnaires and surveys completed by the employees.

There are issues, of course, about subjectivity (what counts as happiness in the mind of any individual) and relativity (compared to what past or recent experiences are they rating the present). There is no consensual definition of happiness, or agreed taxonomy of happiness factors. The challenges for Happiness research are considerable.

Semantics

The fist problem concerns semantics and the sheer breadth of meaning associated with the term. My online thesaurus finds 46 core synonyms for the word ‘happiness’ and a very extensive further vocabulary linked through over 60 other closely associated terms like Bliss, Humour, Comfort, Ease, Ecstasy, Satisfaction, Jubilance, Effervescence, Nirvana, Enjoyment, Exultation, Well-being, Merriment, Luckiness, Optimism and Exultancy. All of this extensive lexicon relates to the concept of happiness and furnishes a wide spectrum of nuanced meanings.

Cognitive traps

In his Ted Talk, the Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman states:

“‘Happiness’ is just not a useful word anymore, because we apply it to too many different things… [there] is a confusion between experience and memory; it’s between being happy in your life, and being happy about your life… Those are two very different concepts, and they’re both lumped in the notion of happiness” Daniel Kahneman (2010).

Kahneman describes a series of ‘cognitive traps’ that make happiness very difficult territory to navigate. He argues that it is almost impossible to think coherently about Happiness (his TED talk well worth viewing).

Psychology of Personality

The Positive Psychology movement has provided much of the up-beat momentum behind the current optimism about creating a happier world. Martin Seligman refers to the good life as “using your signature strengths every day to produce authentic happiness and abundant gratification”. This reference to ‘signature strengths’ implicitly recognises that the happiness agenda is unique for each individual. This is an important point; in the search for happiness we do not all set out from the same starting place. We have each been dealt a different hand of cards at the point of conception and, through nurturing, experience and life circumstances, these cards may be either enhanced or diminished in equipping us to meet the life’s challenges.

Some important individual ‘happiness’ related differences are identified by personality research. Measures of neuroticism make a particularly useful contribution. Also referred to as low Emotional Adjustment, it is a personality characteristic that has well understood involvements with both neurological and physiological mechanisms of emotion. It has implications for the way that life is experienced and coped with. It has an obvious influence on the day to day ‘subjective wellbeing’ of individuals. It is associated with strong feelings; passion, anxiety, fear, moodiness, pessimism and self-doubt at one end of the scale and, at the other, calmness, optimism, self-confidence and evenness of temper. Any attempt to address subjective happiness surely has to recognise these individual differences in personality?

PCL

Whilst investigating the relationship between competence at work and job satisfaction, the implications of potential personality effects in measures of happiness have been picked up in our own research at PCL. We were surprised to discover that expressions of job satisfaction may have more to do with the personality of the respondent than with the ‘goodness of fit’ with their work role. We had expected that high competency scores would be associated with greater job satisfaction and that job satisfaction would therefore differ from job to job. The intriguing finding was that those reporting the highest job satisfaction, whatever the job, tended to be well adjusted extroverts.

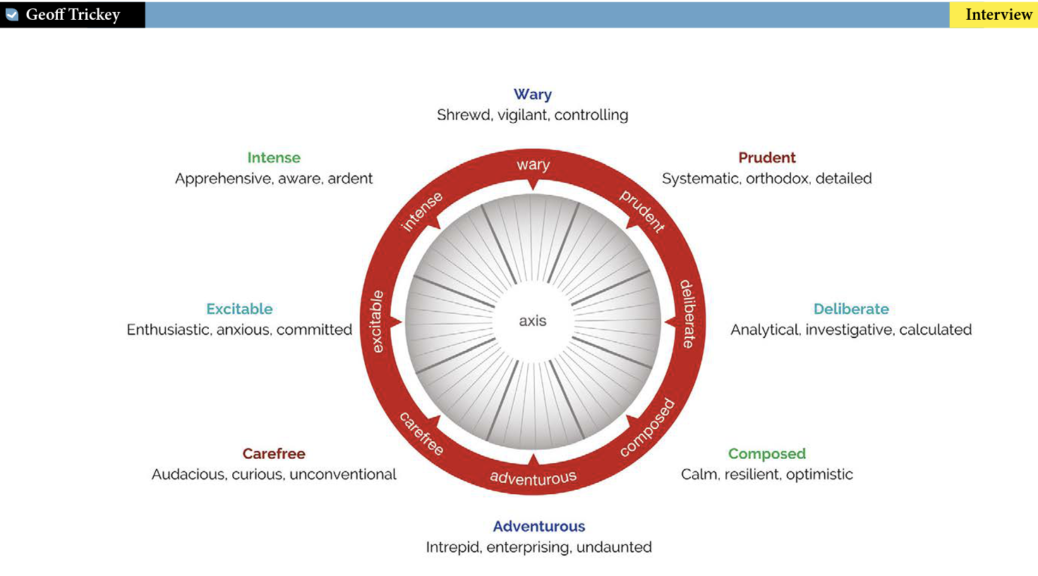

This observation is congruent with the ‘Happy Employee’ concept which differentiates between those disposed to view a challenging job as an opportunity while others are more likely to view it as setting them up to fail (Locke, McClear & Knight, 1996). This is also reflected in our work with Risk Type, differentiating those who are alert to the opportunity in any situation in contrast to those who are more alert to the risk.

It is virtually impossible to know to what extent one person’s experience of happiness equates with another’s but it seems that even in the most awful situations, some will see hope where others will see only doom and gloom. We know too from research into questionnaire design that some people actually prefer to respond ‘yes’ to a question and some prefer to say ‘no’. They are referred to as Yea-sayers or Nay-sayers. Quite literally, the odds are stacked one way or the other before you even ask a question. Asking people whether they are happy, satisfied or engaged in their job is not as revealing as you might think. These ‘response style’ differences illustrate the ways in which personality differences permeate people’s outlook on life.

Any campaign promoting ‘happiness for all’ would be difficult to resist, as would any populist mainstream trend designed to better the human condition. The impulse to sweep aside the irksome detail of scientific discipline to grasp the possibilities offered through refreshing and exciting new lines of thought can seem irresistible and appealingly radical. Promises of savings in public spending are also extremely attractive and support for the happiness campaign has partly been justified by pragmatically economic and political motives; the expected cost of mental health care and loss to productivity.

But the trouble with happiness is how do you pin it down; is it an opinion, a philosophical question, a scientific fact, a belief? To what extent is it cultural, psychological, mental, spiritual, physical or meta-physical? The assertion that ‘if you can’t measure it you can’t manage it’, attributed to the late Peter Drucker, makes an important point. Should we really invest heavily in the idea that we can either achieve objective measures of happiness, or realistically re-deploy already scarce psychological therapeutic techniques and resources on a scale to address issues of national and international unhappiness?

Happiness is a delightful concept of course, who wouldn’t embrace it? But the reasons for unhappiness are innumerable, highly complex, endemic and intransigent. This is not a battle that will be won by optimism and euphoria.

First published on Engage Employee.